By Admin

NanoFuse is a biologic tech company acquired by Dr. Kingsley R. Chin, through his private equity firm KICVentures.

Scientific Paper

James F. Kirk , Gregg Ritter, Michael J. Larson, Robert C. Waters, Isaac Finger, John Waters, John H. Abernethy, Dhyana Sankar, James D. Talton and Ronald R. Cobb

Abstract

Autologous bone has long been the gold standard for bone void fillers. However, the limited supply and morbidity associated with using autologous graft material has led to the development of many different bone graft substitutes. The use of bone graft extenders has become an essential component in a number of orthopedic applications including spinal fusion. This study compares the ability of NanoFUSE® DBM and a bioactive glass product (NovaBone Putty) to induce spinal fusion in a rabbit model. NanoFUSE® DBM is a combination of allogeneic human bone and bioactive glass. NanoFUSE® DBM alone, and in combination with autograft and NovaBone Putty, were implanted in the posterior lateral intertransverse process region of the rabbit spine. The spines were evaluated for fusion at 12 and 24 weeks for fusion of the L4-L5 transverse processes using a total of 64 skeletally mature rabbits. Samples were evaluated by manual palpation, radiographically, histologically, and by mechanical testing. Radiographical, histological, and palpation measurements demonstrated the ability of NanoFUSE® DBM to induce new bone formation and bridging fusion. The material in combination with autograft performed as well as autograft alone. In addition, the combination of allogeneic human bone and bioactive glass found in NanoFUSE® DBM was observed to be superior to the bioactive glass product NovaBone Putty in this rabbit model of spinal fusion. This in vivo study demonstrates the DBM and bioactive glass combination, NanoFUSE® DBM, could be an effective bone graft extender in posterolateral spinal fusions.

Introduction

The use of autograft material remains the gold standard for use in orthopedic procedures due to the fact that there is little chance of immune rejection and its innate osteoconductive, osteoinductive, and osteogenic potential. Due to the significant levels of pain and morbidity at the donor site, bone graft substitutes are commonly used [1-4]. Bone graft substitutes offer a wide range of materials, structures, and delivery systems to be used in bone grafting procedures. Common sources of bone graft materials include allogeneic bone, synthetic calcium phosphate salts, coralline materials and bioactive glass. These materials should possess one or more of the characteristics typical of autograft material including osteoconductivity, osteoinductivity and osteogenicity. Human derived demineralized bone matrix (DBM) has become a very common bone graft substitute which has shown the ability to aid in new bone formation in many different clinical settings including long bone defects, craniofacial reconstruction, and spinal fusion [5-9]. DBM in combination with local bone has been shown to perform as well as autograft, potentially eliminating the need for autogenous bone harvesting [8]. Studies have shown that allogeneic DBM possesses inherent osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties, as well as containing numerous bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) that initiate the cascade of new bone formation [10-13]. There are several commercially available DBM products for use in spinal surgery. Many of these have been tested using rabbit spinal fusion model [14, 15] revealing differences in fusion rates. The different osteoconductive capabilities of these products have been explained as a consequence of the processing methods, as well as the age and quality of the donor bone [11, 16- 24]. NanoFUSE® DBM was created to take advantage of the osteoconductive and proangiogenic properties of bioactive glass as well as the osteoinductive properties of human-derived DBM. The bioactive glass portion of NanoFUSE® DBM is composed of 45S5 composition disclosed by Hench (also known as Bioglass® ). Previous studies have shown that the NanoFUSE® DBM is biocompatible and has both osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties [25]. During the last couple of decades, the development of new implant technologies have shifted from attempts to create a passive interface between the implant and the native tissue to the design of bioactive materials. Within this category are a wide range of synthetic calciumphosphate ceramics, bioactive glass, and bioactive glass-ceramics [26, 27]. Advantages of 4 synthetic materials include tunable resorption rates, increased mechanical strength compared with DBM products, controlled porosity, and ideal processing and molding parameters [28, 29]. Bioactive glass is the first man-made material to form a direct chemical bond with bone. When in contact with surface-reactive bioactive glass, osteoblasts undergo rapid proliferation forming new bone in roughly the same time period as the normal healing process. Bioactive glass has been proven effective in generating new bone in several different pre-clinical animal studies [30- 33], as well as in approved products on the market. In addition, only a minimal amount of bioactive glass is required to induce graft bioactivity. One such bioactive glass based material is the currently marketed NovaBone Putty. Numerous investigations examining implant resorption and bone formation of various bone graft substitutes and extenders have been performed [7, 8, 14, 34-36]. In the present study, NanoFUSE® DBM was evaluated and compared to a bioactive glass based material, NovaBone Putty to induce bone formation and bridging fusion in a rabbit posterolateral spinal fusion model. This animal model has been widely used for evaluating spinal surgery technique and spinal fusion implant materials. The surgery involves fusion of the L4-L5 motion segments without plating or stabilization. Test materials were implanted in the posterior lateral L4-L5 intertransverse process region of the spine and were analyzed for up to 24 weeks.

Materials & Methods

Implant Materials

The NanoFUSE® DBM used for these studies was prepared from DBM derived from the long bones of rabbits. The demineralization process was similar to that described by Urist [12]. The final particle size was a distribution spanning 125 to 710m. Bioactive glass, of the 45S5 composition, was purchased from Mo-Sci Health Care, LLC (Rolla, MO). The composition of the 45S5 (w/w%) was 43 – 47% SiO2; 22.5 – 26.5% CaO; 5 – 7% P2O5; and 22.5 – 26.5% Na2O with a particle size distribution of 90 – 710 µm (≥ 90%). NanoFUSE® DBM was formulated essentially as described [25]. The material was hydrated and warmed immediately prior to implantation. NovaBone Putty was obtained and prepared using aseptic techniques. Autograft was harvested in select animals from the iliac crests and morselized with Rongeur forceps to an approximate diameter of 5 mm or less. The target volume of bone graft material to be placed for each lateral side of the motion segment was 3cc.

Surgical Procedures

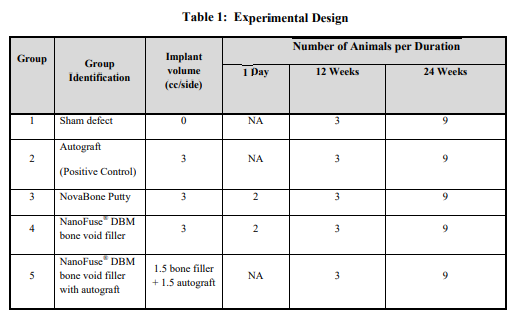

New Zealand White rabbits (64) were obtained from Western Oregon Rabbit Company (Philomath, OR), weighing approximately 4 kg each (Table 1 for experimental design). Animals were acclimated to the facility for a minimum of one week and completed a pre-study physical examination prior to research use. Each rabbit was weighed prior to surgery to enable accurate calculation of anesthesia drug dosages and to provide baseline body weight for subsequent general health monitoring. Glycopyrrolate (0.1 mg/kg) was administered intramuscularly (IM) approximately 15 minutes prior to anesthesia induction to protect cardiac function during general anesthesia. Butorphanol (1.0 mg/kg) and acepromazine (1-2 mg) were also administered for sedation and early post operative analgesia. General anesthesia was induced with an IM injection of ketamine (25-30 mg/kg) and xylazine (7-9 mg/kg), followed by endotracheal intubation. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (0-4%, to effect) in oxygen. A 24 gauge intravenous (IV) catheter was introduced into the marginal ear vein and secured to the skin. Yohimbine (Yobine, Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA), was administered intravenously (0.2 6 solution was administered intravenously at a rate of 10-20 ml/kg/hr during the surgical procedure. A dorsoventral radiographic image of the lumbar spine was obtained prior to operative site preparation to identify the targeted L4-5 operative site. The fur over the operative site was then removed with an electric clipper to expose a sufficient area of skin for aseptic surgery and autograft harvest, if indicated. The skin was subsequently scrubbed with a povidone iodine surgical scrub followed by 70% isopropyl alcohol rinse. This process was repeated at three times. Sites were then painted with a povidone iodine solution. The animal was transferred into the operating room and draped for aseptic surgery. The spine was approached through a single midline skin incision and two paramedian fascial incisions. The L4-L5 levels were identified during surgery by referencing the preoperative radiographic images and iliac crest palpation. The dorsal surfaces of the transverse processes (TPs) of L4 and L5 were then bilaterally exposed and approximately 2 cm of each TP was decorticated with a motorized burr [37] Hemorrhage was controlled with pressure and the judicious use of cautery. The gutters were flushed with 1-2 cc of saline to facilitate removal of bone dust and clots. Approximately 3.0 cc of each material was placed in the paraspinal gutters, forming a continuous bridge over and between the decorticated TPs of L4 and L5. (see Table 1 for experimental design). After the bone graft materials were implanted and TP bridging was verified by visual inspection, the fascia was closed with sutures in two layers and the skin was approximated with staples. The rabbits were recovered from anesthesia with supplemental heat and were returned to their home cages after they became ambulatory. Supplemental butorphanol (1 mg/kg) was administered for pain approximately 3 hours after extubation while fentanyl blood levels increased. At 3, 9 and 18 weeks after surgery, animals were humanely euthanized by intravenous injection of barbiturate solution. The lumbar spines were explanted during necropsy examination and the operative sites were evaluated for fusion using manual palpation, radiography, histological analyses, and mechanical testing.

Manual Palpation

Manual palpation is the gold standard for evaluating posterolateral lumbar fusion in experimental animals. In the present study, first the spines were explanted, and the L4-L5 segment was tested with manual palpation. Two reviewers independently evaluated the spines for fusion in a blinded fashion. Fusion was deemed successful whenever there was no segmental 7 motion between adjacent vertebrae in lateral bending and flexion and extension planes. When reviewers disagreed in their fusion evaluation, a third reviewer evaluated the explanted spines to make the final determination of fusion.

Mechanical Testing

All mechanical testing was performed by Numira Biosciences (Bothell, WA). Six samples from each group from the 24-week time point was be properly stored and then evaluated for uniaxial tensile testing. After the remaining muscle and facet joints were removed, pilot holes were drilled ventral to dorsal through two adjacent vertebral bodies. Just prior to testing, the intervertebral disc was divided with a scalpel so that only the intratransverse membrane and fusion mass was left to connect the two adjacent vertebrae. Stainless steel pins were inserted through the pre-drilled holes and connected to a steel wire attached to the material testing device. Biomechanical testing was performed using an Instron 5500R running Bluehill version 2.5 software. Using the jog up controller, each sample was brought to a point where no slack was present in the steel wires hooked to the pins. A tension load was applied to the specimen at a rate of 6mm/min until failure. To obtain maximum load, the cursor was placed at the peak of the load extension curve. To obtain stiffness, the steepest part of the load extension curve was identified and the cursor was placed at the lower end of the slope and then at the upper end. Stiffness was determined as the slope of this line. To obtain energy, if the curve continued to rise without a break or pause in the load-extension curve, the cursor was placed at the point where the curve began to rise and then at the point of the maximum load. If there was a break or pause in the load-extension curve, the cursor was placed at the point where the load-extension curve began to rise, then at the point where the load-extension curve began to pause, then at the point where the pause ended, and finally at the point of maximum load. Energy is the area under the curve, which is the sum of two energy values if there is a pause in the curve. Following cursor placement, the software performed the calculations and displayed the results. The software provided Maximum Load, Stiffness, Energy, and Extension (at Maximum Load).

Radiographic Assessment

Posteroanterior radiographs were performed immediately after surgery, and at approximately 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 weeks post surgery. Radiographic images were evaluated for evidence of new bone growth, implant integration and radiographic fusion, defined as mineralized or trabecular bone bridging between the transverse processes of the L4-L5 lumbar 8 vertebrae. Images that were graded as fused were determined to have a mineralized bone bridge between the L4-L5 vertebrae. Images that were graded as not fused may have demonstrated considerable new bone in the L4-L5 interspaces, thin radiolucent fissures transversing the fusion masses or radiolucent zones near the vertebrae, interrupting what would otherwise have been a continuous bone bridge between the transverse processes. Images demonstrating significant radiodensity from the implants were graded as ‘fusion indeterminate’ and were not included in the fusion scores.

Histopathology

Three animals per group will be utilized for histological evaluations. Processing of the slides was performed by Laudier Histology (New York, NY). Freshly prepared samples of implant material were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in methyl methacrylate, and then sectioned 5m thick. The sections were stained with toluidine blue to visualize new bone and cartilage formation. Histological scoring was performed based on bilateral assessment as described in Table 2. Pathologic evaluation was performed for the implant sites to determine degree of new bone development in the implant sites as well as to determine spinal fusion (bridging bone)

Results

Surgery

Sixty four (64) animals underwent surgery for this study (see Table 1 for experimental design), but a total of 63 survived the study. One sham treated animal died one week postsurgery and was not replaced. The rabbits recovered well from the general anesthesia and weight gain patterns throughout the study were normal. After several days, surviving rabbits were ambulating normally and demonstrated normal appetites and behavior patterns. These patterns remained normal for the study term.

Manual Palpation

Stiffness of the fused motion segment was assessed by manual palpation. The fusion was graded by two independent blinded observers. If no detectable motion was observed, this was graded as fused. The spines that demonstrated motion between the L4-L5 vertebrae were graded as not fused. As shown in Table 3, the sham control group did not demonstrate any spinal fusion at all time points. NovaBone Putty did not demonstrate any spinal fusion at all time points. The NanoFUSE® DBM group alone demonstrated 11% (1/9) fusion rate at the 24 week time point. The NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft group demonstrated similar levels of fusion rates (56% – 5/9) when compared to the autograft alone group (67% – 6/9). At the 12 week time point, only the autograft group demonstrated any spinal fusion (2/2) while all other groups demonstrated 0% fusion (0/3).

Mechanical Testing

During preparation of the specimens, the facet joint (dorsal elements) connecting the vertebrae at the fusion level on one specimen from the NanoFUSE® DBM only group was not removed. Data from this one sample reflects the strength of both the fusion mass and the dorsal elements and therefore was removed from the dataset. The patterns of the data were similar for maximum load (Table 4) with autograft and NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft demonstrating the highest scores. As shown, each of the treatment groups had higher maximum load compared to the sham control group. The maximum load was 159.77±44.58 N for the Sham group, 229.32±94.44 N for the autograft group, 198.69±136.65N for the NovaBone Putty group, 173.00±19.5 N for the NanoFUSE® DBM group and 248.92±74.74 N for the NanoFUSE® DBM+autograft group. However, these differences were not statistically significant. In a similar fashion, autograft and NanoFUSE® 10 DBM plus autograft demonstrated the highest stiffness scores. NanoFUSE® DBM alone had only slightly higher stiffness scores than the sham group, but was higher than the scores observed for NovaBone Putty. It is interesting to note that only the NovaBone Putty had scores that were lower than the sham group with respect to stiffness. The stiffness values were 62.62±16.86 N/mm for the sham group, 90.39±18.39 for the autograft group, 50.24±28.34N/mm for the NovaBone Putty group, 69.04±26.68 N/mm for the NanoFUSE® DBM group and 85.14±9.52 N/mm for the NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft group. However, these differences were not statistically significant. NovaBone Putty demonstrated the highest extension scores. With respect to the other groups, there was little effect of treatment on extension. The extension values were 6.27±1.38 cm for the sham group, 5.13±2.73 cm for the autograft group, 8.45±3.91cm for the NovaBone Putty group, 5.99±1.69 cm for the NanoFUSE® DBM group and 5.70±1.37 cm for the NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft group. However, these differences were not statistically significant. NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft had the highest scores with respect to energy. NanoFUSE® DBM alone and autograft had similar numbers which were higher than the sham controls. NovaBone Putty had energy scores that were lower than the sham controls. The energy values were 299.33±123.32 mJ for the sham group, 339.21±283.28 mJ for the autograft group, 207±139.33 mJ for the NovaBone Putty group, 393.08±138.13 mJ for the NanoFUSE® DBM group alone, and 514.81±252.32 mJ for the NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft group. However, these differences were not statistically significant. Overall, the load, stiffness, extension, and energy for NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft were equivalent to the pure autograft, however the NanoFUSE® DBM alone demonstrated lower values for stiffness, extension, and load which were similar to the sham controls. NovaBone Putty demonstrated lower scores than the sham treated animals in stiffness and energy, but had the highest scores of all treatment groups with respect to extension.

Radioactive Analyses

Radiographic images generated for this study were evaluated for evidence of new bone growth, implant integration and radiographic fusion, defined as mineralized or trabecular bone bridging between the transverse processes of the operated segments. Radiographic fusion was judged by continuous trabecular bridge between L4-L5 transverse processes. Each side was scored independently and had to have continuous bridging bone between the transverse processes 11 to be scored as fused (Figures 1 and 2). Images demonstrating significant radiodensity from the implants were graded as “fusion indeterminate” and were not scored as fusion. At 4 weeks, the autograft group demonstrated 79% (19/24) fusion while the NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft demonstrated a 54% (13/24) fusion rate (Table 5). NanoFUSE® DBM alone and the sham control did not demonstrate any fusion at this time point. All samples from the NovaBone Putty demonstrated significant radiodensity from the implant material and were scored as “fusion indeterminate.” At 8 weeks, the autograft group demonstrated 92% (22/24) fusion rate while the NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft demonstrated a 75% fusion rate (18/24). Fusion was observed in the NanoFUSE® DBM alone group at eight weeks (4/24, 17%). No fusion was observed for either the sham or NovaBone Putty groups. Ten segments from the NovaBone Putty group demonstrated significant radiodensity and were scored as “fusion indeterminate.” By 12 weeks, the autograft and NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft groups demonstrated similar fusion rates. Fusion was observed in the NanoFUSE® DBM alone group (7/24, 29%) while no fusion was observed in the sham or NovaBone Putty groups. By 18 and 24 weeks, autograft and NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft demonstrated similar levels of fusion. The levels of fusion for the NanoFUSE® DBM alone group were similar in both the 18 and 24 week time points (56% and 61%, respectively). No fusion was observed in the sham or NovaBone Putty groups at the 18 and 24 week time points.

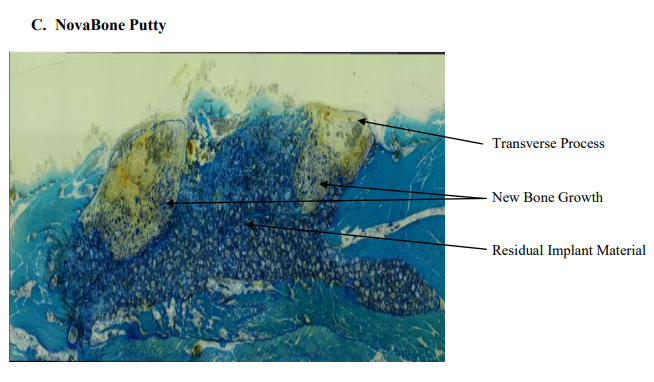

Histological Evaluation

Histologic results showed that all test articles were well tolerated in the test animal. There was no significant inflammation or foreign body giant cell response. Histologic data are provided in Table 6 and representative images are found in Figure 3 (12 week time point) and Figure 4 (24 week time point). Implant sites from all animals at the 12 week time point from the sham group , consisted of variable amounts of new bone with bone marrow, fibrosis and adipose tissue. New bone growth that was observed consisted of a minimal to mild amount of new bone and bone marrow. Two of the implant sites contained a minimal amount of cartilage. In addition, a minimal amount of neovascularization and adipose tissue infiltration was observed. A representative slide from this group is found in Figure 4A. The tissue samples from the autograft group consisted of new bone, bone marrow, fibrosis and adipose tissue at the 12 week time point. Three samples from this group demonstrated 51-100% of bridging of the defect with new bone. The new bone in all of the 12 implant sites consisted of minimum to mild amounts of new bone and a minimal to marked amount of bone marrow. The tissue reaction of these samples contained a minimal number of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. A representative slide from this group is shown in Figure 3B. The autograft samples from the 24 week group demonstrated very little evidence of the implant material. The samples contained 51-100% of bridging of the defect site with new bone with a moderate amount of bone marrow. A minimal amount of neovascularization was observed in the tissue samples from this group. The tissue reaction of the samples contained a minimal number of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. A representative slide from this group is presented in Figure 4B. At the 12 week time point, NovaBone Putty implant sites contained a significant amount of residual implant material (76-100%). The implanted material consisted of many variably sized closely packed pieces of pale blue anuclear material. The implant material was found within the new bone growth. All of the 12-week implant sites had 1-25% of bridging of the defect with new bone. The new bone consisted mainly of a minimal amount of new bone and bone marrow. The tissue reaction of the samples contained minimal numbers of lymphocytes. The minimal amount of adipose tissue that was observed was a healing response of the muscle tissue adjacent to the implant sites. A representative slide from this group is presented in Figure 3C. The 24 week NovaBone Putty implant sites consisted mainly of the implant material, new bone and bone marrow. All of the implant sites contained moderate levels of residual implant material (51-75%). The implant material consisted of many variably sized closely packed pieces of clear to pale blue anuclear material. The implant material was surrounded and divided by the fibrosis and chronic inflammatory cells. The samples contained 1-25% of bridging bone across the defect and the percentage of the implant site occupied by new bone was 1-25%. The tissue reaction of all of the NovaBone Putty implant sites contained a moderate number of macrophages and a minimal to mild number of multinucleated giant cells. The adipose tissue that was observed was a healing response of the muscle tissue adjacent to the implant sites. A representative slide is presented in Figure 4C. At the 12 week time point, the NanoFUSE® DBM implant sites contained a minimal amount of implanted material (1-25%). The implanted material consisted of small fragments of light blue anuclear material. The implant material was found within the new bone growth. There was 51-99% bridging of the defect with new bone and the percentage of the implant site 13 occupied by new bone was 26-75%. The new bone consisted of a minimal amount of new bone and a moderate amount of bone marrow. The tissue reaction of these sites contained a minimal number of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells and a minimal amount of adipose tissue. A representative slide is presented in Figure 3D. The NanoFUSE® DBM group samples at the 24 week time point contained a minimal amount (1-25%) of the implanted material. The implanted material consisted of small fragments of light blue anuclear material. The implant consisted of a minimal amount of new bone with a minimal to moderate amount of bone marrow and adipose tissue. The implant sites had 1-25% or 100% bridging of the defect with new bone and the percentage of the implant site occupied by new bone was 1-25% or 76-100%. The tissue reaction of all the samples contained a minimal number of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. A representative slide from this group is presented in Figure 4D. The NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft group implants at the 12 week time point contained a minimal amount (1-25%) of the implanted material. The implanted material consisted of small fragments of light blue anuclear material. The implant sites consisted of a minimal to mild amount of new bone, a mild amount of bone marrow and adipose tissue. There was 51-100% bridging of the defect with new bone and the percentage of implant sites occupied by new bone was 51-75%. The tissue reaction to these implants contained a minimal to mild amount of adipose tissue, a minimal number of macrophages, and a minimal number of multinucleated cells. A representative slide is shown in Figure 3E. At the 24 week time point, the NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft group implant sites contained a minimal to mild amount of new bone and a mild to moderate amount of bone marrow. A minimal amount (1-25%) of the implanted material was still visible as variably sized closely packed pieces of pale blue anuclear material. All of the implant sites in this group had 100% bridging of the defect with new bone and the percentage of the implant site occupied by new bone was 51-100%. There was also a minimal amount of neovascularization observed. The tissue reaction of all the implants contained a minimal number of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. A representative slide is presented in Figure 4E.

Discussion

The need for bone graft materials is an ongoing challenge in orthopedics. Many different biomaterials are becoming available for use in orthopedic reconstruction [38, 39]. The use of commercially available DBM as a supplement to autogenous bone is becoming increasingly common [7, 8, 15, 40]. However, autogenous bone remains the gold standard for use in orthopedic procedures due to its osteoinductive, osteoconductive, and osteogenic potential. Due to postoperative morbidity, and in revision cases where the autogenous iliac crest bone graft is limited, the search continues for effective alternatives. The development of novel bone graft substitutes with novel properties can expand the use of these materials in orthopedic treatments. Bone graft substitutes should possess one or more of the characteristics typical of autograft. These materials should be biocompatible, possess osteoconductive as well as osteoinductive properties, and should degrade in concert with bony replacement. Bioactive glass is the first man-made material to form a direct chemical bond with bone. It is also the first man-made material to exert a positive effect on osteoblastic differentiation and osteoblast proliferation [41]. The composition of the bioactive glass portion of NanoFUSE® DBM is the same as that of Hench’s Bioglass. Years of testing, preclinical, and clinical use have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this material [42]. Bioactive glass has traditionally been employed for its osteoconductive and osteostimulative properties [41, 43, 44]. Recently, data has been presented demonstrating the proangiogenic potential of bioactive glass in vitro and in vivo [44]. In addition, these studies have shown that the soluble dissolution products of bioactive glass can stimulate the production of proangiogenic factors, thereby providing a potentially promising strategy to enhance neovascularization and resultant bone formation. Wheeler et al demonstrated equivalent rates of bone growth for bioactive glass particles, for autograft, and reported rapid proliferation of bone in contact with the bioactive glass particles [33]. Further studies have shown that new bone occupied an average of 50% of the femoral condyle defect area at three weeks in a group of animals treated with a phase pure porous silicate-substituted calcium phosphate ceramic [45]. Additional studies have suggested that Bioglass particles may have advantages over other bone graft substitute materials [33, 46]. In contrast, an evaluation of 45S5 bioglass for osteoconductive and osteoinductive effects in a calvarial defect demonstrated only 8% new bone formation and various degrees of inflammation [47]. Other authors also 15 described multinuclear giant cells associated with Bioglass particles in a rabbit distal femur model [48]. Previous studies have demonstrated the biocompatibility of the NanoFUSE® DBM material [25]. These studies also demonstrated that NanoFUSE® DBM materials meet the criteria for an ideal bone graft, namely because they possess osteoconductive as well as osteoinductive properties, degrade in concert with bony replacement, and are biocompatible. NanoFUSE® DBM combines the osteoconductive and proangiogenic properties of bioactive glass with the osteoinductive properties of human DBM. While each of these is important, it is the osteoinductive nature of DBM that enables bone generation to occur throughout a defect rather than simply at the edges [6]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate and compare the capacity of NanoFUSE® DBM and NovaBone Putty to induce osteogenesis and bridging fusion in a rabbit spinal fusion model. Test materials were implanted in the posterolateral inter-transverse process region of the spine and analyzed at various different time points. Samples were evaluated radiographically, histologically, by manual palpation, and by mechanical strength testing. Similar models have been used to verify autograft extenders with reproducible results. The manual palpation rate of 67% observed in the autograft control group is consistent with the rate demonstrated in previous studies [37, 49-53]. NanoFUSE® DBM in combination with autograft demonstrated increased fusion rates when compared to sham controls. NanoFUSE® DBM in combination with autograft demonstrated equivalent fusion rates when compared to autograft controls when measured with manual palpation or radiographically. The ability of NanoFUSE® DBM to homogeneously mix with the morselized autograft allowed a continuous mixture of substrate with minimal void within the graft site for new bone to develop and fuse the motion segment. Radiographic analyses also showed similar fusion rates when NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft and autograft. In addition, implant sites from NanoFUSE® DBM alone group demonstrated >50% fusion rates as determined by radiographic analyses. In contrast, no fusion was observed either by manual palpation or radiographic methods for animals treated with NovaBone Putty. The results of this rabbit spinal fusion study demonstrate the biocompatibility of the NanoFUSE® DBM material. They also demonstrate that the NanoFUSE® DBM material is significantly resorbed (only 1-25% of the implanted material being observed) and replaced with 16 new bone within 24 weeks. The results also suggest that NanoFUSE® DBM is effective in producing a posterolateral fusion by radiographic and manual palpation criteria in an extender mode. This study demonstrates radiographically, histologically, and by manual palpation assessment the ability of NanoFUSE® DBM to induce new bone formation and bridging fusion comparable to autograft in the rabbit spinal fusion model. NanoFUSE® DBM performed well as an autograft extender application and as a stand-alone bone graft substitute in a rabbit model. Similarly, biomechanical data showed comparable values for load, stiffness, extension and energy between NanoFUSE® DBM plus autograft and autograft alone. While animal models cannot be translated into clinically successful human applications, the results of this study suggest further investigation into the clinical use of this material either as a stand-alone bone void filler or as a graft extender is warranted. NanoFUSE® DBM is a registered trademark of Nanotherapeutics, Inc.

Figure Legends

Figure 1: Representative radiographs of spines from 12-week samples. (A) sham; (B) autograft; (C) NovaBone Putty; (D) NanoFUSE® DBM; (E) NanoFUSE® DBM+autograft.

Figure 2: Representative radiographs of spines from 24-week samples. (A) sham; (B) autograft; (C) NovaBone Putty; (D) NanoFUSE® DBM; (E) NanoFUSE® DBM+autograft.

Figure 3: Representative histological slides of spines from 12-week samples. Freshly prepared samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in methyl methacrylate and then sectioned 5m thick. The sections were stained with toluidine blue. (A) Representative slide of a Group 1 (Sham Defect) 12 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification; (B) Representative slide of a Group 2 (Autograft (Positive Control)) 12 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification. ; (C) Representative slide of NovaBone Putty 12 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification; (D) Representative slide of a NanoFuse® DBM 12 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification. : (E) Representative slide of a NanoFUSE® DBM with Autograft 12 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification.

Figure 4: Representative histological slides of spines from 24-week samples. Freshly prepared samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in methyl methacrylate and then sectioned 5m thick. The sections were stained with toluidine blue. Slides were fixed in 10% (A) sham; (B) Representative slide of an Autograft Positive Control 24 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification; (C) Representative slide of NovaBone Putty 12 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification; (D) Representative slide of a NanoFuse® DBM 24 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification. ; (E) Representative slide of NanoFUSE® DBM with Autograft 24 week implant site – whole implant site photo at 20x magnification.

About the LESS Institute’s Dr. Kingsley R. Chin

Dr. Kingsley R. Chin is a board-certified Harvard-trained orthopedic spine surgeon and professor with copious business and information technology experience. He sees a niche opportunity where medicine, business and information technology meet and is uniquely experienced at the intersection of these three professions. He currently serves as Professor of Clinical and Biomedical Sciences at the Charles E. Schmidt School of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University and Professor of Clinical Orthopaedic Surgery at the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University and has experience as Assistant Professor of Orthopaedics at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School and Visiting Professor at the University of the West Indies.

Learn more about Dr. Chin here and connect via LinkedIn.

Scientific Paper Author & Citation Details

Dr. Kingsley R. Chin, founder of philosophy and practice of The LES Society and The LESS Institute

Authors

James F. Kirk1, Gregg Ritter1, Michael J. Larson2, Robert C. Waters1, Isaac finger1, John Waters1, John H. Abernethy1, Dhyana Sankar1, James D. Talton1 and Ronald R. Cobb1

Author information

Research and Development Department, Nanotherapeutics, Inc., Alachua, FL

Ibex Preclinical Research, Inc., Logan, UT 84321

References Cited

Goulet, J.A., et al., Autogenous iliac crest bone graft. Complications and functional assessment. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1997(339): p. 76-81.

Heary, R.F., et al., Persistent iliac crest donor site pain: independent outcome assessment. Neurosurgery, 2002. 50(3): p. 510-6; discussion 516-7.

Ubhi, C.S. and D.L. Morris, Fracture and herniation of bowel at bone graft donor site in the iliac crest. Injury, 1984. 16(3): p. 202-3

Younger, E.M. and M.W. Chapman, Morbidity at bone graft donor sites. J Orthop Trauma, 1989. 3(3): p. 192-5.

Glowacki, J., et al., Application of the biological principle of induced osteogenesis for craniofacial defects. Lancet, 1981. 1(8227): p. 959-62.

Mulliken, J.B., et al., Use of demineralized allogeneic bone implants for the correction of maxillocraniofacial deformities. Ann Surg, 1981. 194(3): p. 366-72.

Rosenthal, R.K., J. Folkman, and J. Glowacki, Demineralized bone implants for nonunion fractures, bone cysts, and fibrous lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1999(364): p. 61-9

Sassard, W.R., et al., Augmenting local bone with Grafton demineralized bone matrix for posterolateral lumbar spine fusion: avoiding second site autologous bone harvest. Orthopedics, 2000. 23(10): p. 1059-64; discussion 1064-5

Tiedeman, J.J., et al., The role of a composite, demineralized bone matrix and bone marrow in the treatment of osseous defects. Orthopedics, 1995. 18(12): p. 1153-8

Mulliken, J.B., L.B. Kaban, and J. Glowacki, Induced osteogenesis–the biological principle and clinical applications. J Surg Res, 1984. 37(6): p. 487-96.

Urist, M.R., R.J. DeLange, and G.A. Finerman, Bone cell differentiation and growth factors. Science, 1983. 220(4598): p. 680-6.

Urist, M.R. and T.A. Dowell, Inductive substratum for osteogenesis in pellets of particulate bone matrix. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1968. 61: p. 61-78.

Urist, M.R. and B.S. Strates, Bone formation in implants of partially and wholly demineralized bone matrix. Including observations on acetone-fixed intra and extracellular proteins. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1970. 71: p. 271-8

Martin, G.J., Jr., et al., New formulations of demineralized bone matrix as a more effective graft alternative in experimental posterolateral lumbar spine arthrodesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1999. 24(7): p. 637-45.

Morone, M.A. and S.D. Boden, Experimental posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion with a demineralized bone matrix gel. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1998. 23(2): p. 159-67.

Edwards, J.T., M.H. Diegmann, and N.L. Scarborough, Osteoinduction of human demineralized bone: characterization in a rat model. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1998(357): p. 219-28

Grauer, J.N., et al., Posterolateral lumbar fusions in athymic rats: characterization of a model. Spine J, 2004. 4(3): p. 281-6

Lee, J.H., et al., Biomechanical and histomorphometric study on the bone-screw interface of bioactive ceramic-coated titanium screws. Biomaterials, 2005. 26(16): p. 3249-57.

Peterson, B., et al., Osteoinductivity of commercially available demineralized bone matrix. Preparations in a spine fusion model. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2004. 86-A(10): p. 2243-50

Adkisson, H.D., et al., Rapid quantitative bioassay of osteoinduction. J Orthop Res, 2000. 18(3): p. 503-11.

Desikan, R.S., et al., Automated MRI measures predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging, 2010. 31(8): p. 1364-74.

Glowacki, J., A review of osteoinductive testing methods and sterilization processes for demineralized bone. Cell Tissue Bank, 2005. 6(1): p. 3-12.

Han, B., B. Tang, and M.E. Nimni, Quantitative and sensitive in vitro assay for osteoinductive activity of demineralized bone matrix. J Orthop Res, 2003. 21(4): p. 648-54.

Lomas, R.J., et al., An evaluation of the capacity of differently prepared demineralised bone matrices (DBM) and toxic residuals of ethylene oxide (EtOx) to provoke an inflammatory response in vitro. Biomaterials, 2001. 22(9): p. 913-21

Kirk, J.F., et al., Osteoconductivity and osteoinductivity of NanoFUSE((R)) DBM. Cell Tissue Bank, 2013. 14(1): p. 33-44.

Hattar, S., et al., Behaviour of moderately differentiated osteoblast-like cells cultured in contact with bioactive glasses. Eur Cell Mater, 2002. 4: p. 61-9.

Kokubo, T., et al., Ca,P-rich layer formed on high-strength bioactive glass-ceramic A-W. J Biomed Mater Res, 1990. 24(3): p. 331-43.

Hak, D.J., The use of osteoconductive bone graft substitutes in orthopaedic trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2007. 15(9): p. 525-36.

Moore, W.R., S.E. Graves, and G.I. Bain, Synthetic bone graft substitutes. ANZ J Surg, 2001. 71(6): p. 354-61

Fujishiro, Y., L.L. Hench, and H. Oonishi, Quantitative rates of in vivo bone generation for Bioglass and hydroxyapatite particles as bone graft substitute. J Mater Sci Mater Med, 1997. 8(11): p. 649-52.

Oonishi, H., et al., Particulate bioglass compared with hydroxyapatite as a bone graft substitute. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1997(334): p. 316-25

Wheeler, D.L., et al., Assessment of resorbable bioactive material for grafting of critical-size cancellous defects. J Orthop Res, 2000. 18(1): p. 140-8.

Wheeler, D.L., et al., Effect of bioactive glass particle size on osseous regeneration of cancellous defects. J Biomed Mater Res, 1998. 41(4): p. 527-33.

Biswas, D., et al., Augmented demineralized bone matrix: a potential alternative for posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ), 2010. 39(11): p. 531-538.

Dodds, R.A., et al., Biomechanical and radiographic comparison of demineralized bone matrix, and a coralline hydroxyapatite in a rabbit spinal fusion model. J Biomater Appl, 2010. 25(3): p. 195-215

Moore, S.T., et al., Osteoconductivity and Osteoinductivity of Puros(R) DBM Putty. J Biomater Appl, 2010.

Boden, S.D., J.H. Schimandle, and W.C. Hutton, An experimental lumbar intertransverse process spinal fusion model. Radiographic, histologic, and biomechanical healing characteristics. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1995. 20(4): p. 412-20.

Bauer, T.W., Bone graft substitutes. Skeletal Radiol, 2007. 36(12): p. 1105-7.

Bauer, T.W. and G.F. Muschler, Bone graft materials. An overview of the basic science. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2000(371): p. 10-27.

Berven, S., et al., Clinical applications of bone graft substitutes in spine surgery: consideration of mineralized and demineralized preparations and growth factor supplementation. Eur Spine J, 2001. 10 Suppl 2: p. S169-77

Xynos, I.D., et al., Bioglass 45S5 stimulates osteoblast turnover and enhances bone formation In vitro: implications and applications for bone tissue engineering. Calcif Tissue Int, 2000. 67(4): p. 321-9

Wilson, J., et al., Toxicology and biocompatibility of bioglasses. J Biomed Mater Res, 1981. 15(6): p. 805-17.

Xynos, I.D., et al., Ionic products of bioactive glass dissolution increase proliferation of human osteoblasts and induce insulin-like growth factor II mRNA expression and protein synthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2000. 276(2): p. 461-5

Xynos, I.D., et al., Gene-expression profiling of human osteoblasts following treatment with the ionic products of Bioglass 45S5 dissolution. J Biomed Mater Res, 2001. 55(2): p. 151-7.

Hing, K.A., L.F. Wilson, and T. Buckland, Comparative performance of three ceramic bone graft substitutes. Spine J, 2007. 7(4): p. 475-90.

Wilson, J. and S.B. Low, Bioactive ceramics for periodontal treatment: comparative studies in the Patus monkey. J Appl Biomater, 1992. 3(2): p. 123-9.

Moreira-Gonzalez, A., et al., Evaluation of 45S5 bioactive glass combined as a bone substitute in the reconstruction of critical size calvarial defects in rabbits. J Craniofac Surg, 2005. 16(1): p. 63- 70.

Vogel, M., et al., In vivo comparison of bioactive glass particles in rabbits. Biomaterials, 2001. 22(4): p. 357-62.

Bozic, K.J., et al., In vivo evaluation of coralline hydroxyapatite and direct current electrical stimulation in lumbar spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1999. 24(20): p. 2127-33.

Lehman, R.A., Jr., et al., The effect of alendronate sodium on spinal fusion: a rabbit model. Spine J, 2004. 4(1): p. 36-43

Liao, S.S., et al., Lumbar spinal fusion with a mineralized collagen matrix and rhBMP-2 in a rabbit model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2003. 28(17): p. 1954-60

Long, J., et al., The effect of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors on spinal fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2002. 84-A(10): p. 1763-8.

Tay, B.K., et al., Use of a collagen-hydroxyapatite matrix in spinal fusion. A rabbit model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1998. 23(21): p. 2276-81.